Take me there

You’re diving where?

When I told friends in Hong Kong that I was going diving in French Polynesia, I invariably got this reply.

It’s understandable. My own geographical knowledge of the Pacific Islands was hazy too. It is a huge, remote, and sparsely populated region. It’s somewhere that I associated with exotic honeymoons or historical seafaring exploits, but not somewhere I ever really thought I would actually go myself, until last year.

So, to answer the question, French Polynesia is here:

At first glance, this doesn’t really help, because you have to scroll right out to see that this French overseas territory, is actually in the South Pacific, is formed of 118 islands across five archipelagos, and covers a vast area the size of Europe! Tahiti, the biggest island, is where you land when you take an international flight. Other than Tahiti, you might be able to name the island of Bora Bora, the luxury travel mecca with its upscale resorts and bungalows on stilts. But that’s not where my dive buddies and I were headed, because that’s not where the best diving is.

A coral atoll from the air

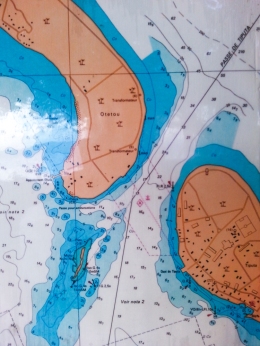

From Tahiti, we took an internal flight to the Tuamotus, a broad, scattered group of coral islands to the north-east of Tahiti. All of the islands are coral atolls, thin, flat strips of land encircling turquoise lagoons. (If you’re interested, here’s how these curious islands are formed). We spent nearly three weeks there split between two of these atolls, Rangiroa and Fakarava, both of them idyllic, pristine, and blessed with out-of-this-world diving.

Diving in the Tuamotus

I’ll be clear: divers don’t go to French Polynesia for the macro. At different locations and times of year, you can see humpback whales, dolphins, mobulas, mantas, and countless species of sharks — it’s basically a paradise for fans of big stuff (and who isn’t?). Our target for this diving trip was the great hammerhead, which can be seen from December to March in Rangiroa. We weren’t disappointed — but more on that later!

Grey reef shark. There are a lot more where he came from.

Tiputa Pass, Rangiroa

All of the dives we did in Rangiroa and Fakarava were in or around passes, i.e. channels where water from the ocean enters the lagoon as the tide is coming in, and exits as the tide goes out. (Geologically, such passes are places where, millions of years ago, there would have been a river mouth on the volcanic island that predates the atoll reef — one of many interesting explanations I owe to Yves Lefèvre, one of our dive guides in Rangiroa.)

Diving in a pass makes for spectacular and effortless drift dives, with strong currents at times. The sea conditions can be pretty rough outside the lagoon with large swells and waves and whirlpools forming as a result of the volume of water being forced through the passes, especially in Rangiroa. The water may be warm and the visibility excellent but sea conditions are not easy for beginners, and it is vitally important to follow the dive guides’ instructions.

Foamy surf from waves seen from below the surface. The swell is very strong here.

The reason many of the dives are conducted at the passes is because of the sheer volume of marine life to be seen. Many species of reef fish gather in passes to reproduce, where the strong currents can carry the fertilised spawn out to the open ocean. After completing their pelagic stage, juvenile fish then return to the lagoon, which serves as a sheltered nursery until they become adults. Because of the abundance of fish, there is plenty of food for the bigger predators in these areas too, so all members of the food chain from the tiniest alvin to the biggest carnivore can seen in these zones. The passes are hotspots of marine life and make for very rich and exciting dives.

Whitetip reef shark and bigeyes

Observations

Another absolute treat for divers, especially underwater photographers, is that the fish are not really afraid of you. On my local dives in Hong Kong, or frequent visits to the Philippines, however gently you approach, many reef fish will swim away more or less quickly once you get within a certain distance. In French Polynesia, I found that this distance was greatly reduced to the point of being non-existent for certain species, and by finning very gently, it is possible to find oneself in the middle of a school of fish without really seeming to disturb them.

Mobbed by ‘sergeant major’ damselfish

On the other hand, coral diversity is poorer. Once again, I am making a comparison with my usual diving playground of the Philippines, which is located in the ‘coral triangle’, with the highest reef biodiversity in the world. Yves explained that as you move east into the Pacific, species diversity decreases. Notably absent in French Polynesia were the huge sea fans, myriad soft corals, sea whips and giant sponges so common on reefs in the Philippines and the South China Sea. Perhaps the onslaught of the Pacific day after day may also have an impact on the ability of certain soft species so grow. At the dive sites we visited, the corals were all hard corals, with just a few predominant species. The effect is that of a less colourful, more homogenous reefscape, but the sheer numbers of fish make up for the bleaker scenery.

Whitecheek surgeonfish in coral feeding frenzy

Why?

I began to wonder why it was so much more fishy — and sharky — in French Polynesia compared to the other places I have dived, and also why the fish are so fearless. I had time to think about these questions during my stay and talk to my hosts, dive guides, and other Polynesian people I met and I came to some conclusions — human ones:

- A pretty small population to sustain — The total population of French Polynesia is around 300,000 people. Although the major source of food is the sea, with such a vast area, there is more than enough for all the apex predators: humans, sharks and dolphins. The human demand on fish stocks is very small, compared to, say, Hong Kong’s waters, which is a minute fraction of the size with a population more than 20 times greater.

- Sustainable fishing practices — local fishermen use fish traps and line fishing methods. The harmful fishing techniques such as dynamite and cyanide which have damaged so many reefs in South East Asia are mercifully unheard of here. There are some commercial fishing operations but these are out at sea but not near the reefs we visited. Fish do not see humans as a threat and so are unafraid.

- Relatively fewer divers — I generally think that divers have a positive impact on the ocean, since these are people who have actually seen what is there and tend to naturally act as ambassadors, but nevertheless divers do cause localized damage, especially at popular dive sites, and their behaviour can alarm fish who learn to be wary. During our dives in French Polynesia, we rarely saw other groups, and there are very few dive shops which puts a cap on the numbers of diving tourists. The expense of simply getting there is another factor which is perhaps bad for the local economy but certainly good for the ocean.

There is probably a whole combination of factors to explain why the sea in French Polynesia is very healthy and apparently well protected, perhaps political ones as well as geographic, demographic and economic ones. Whatever the reasons, diving here allowed me to witness what a healthy reef should look like and what the ocean can offer if we are willing to protect it.

Yellowfin goatfish school

Update: detailed write-up and a photo gallery of both Rangiroa and Fakarava are now published. Click the links to take a look.

Further info

(There is detailed info about these dive shops and locations in the subsequent posts. All were superb, and I’d use them again)

- Dive shop in Rangiroa: Raie Manta Club

- Dive shop in Fakarava: Kaina Plongee (Fakarava Diving Center)

- Guesthouse in Rangiroa: Pension Tapuheitini

- Guesthouse in Fakarava: Pension Vaiama Village

- Flights from Hong Kong to Papeete via Auckland with Air New Zealand.

- Internal flights from Papeete to the Tuamotus with Air Tahiti Nui.

If you enjoyed this post, please do follow this site by ‘liking’ its facebook page to receive future updates, or subscribe by email (scroll down, bottom right). Thank you!

Thank you so much to share all these information about French Polynesia, I’m really looking forward to reading your next posts. You’re so lucky to be based in Hong Kong, Pacific Islands are really too far away from Europe. But maybe one day, when I’ll be geographically closer to you (my next big target is Japan).

LikeLike

Actually the Pacific is still a very long travel from Hong Kong – 10.5 hours to Auckland, 5 hours to Papeete and then another hour to Rangi / Faka islands. But travelling from Europe it is even further, indeed. Maybe you could include French Polynesia on a round the world trip!

LikeLiked by 1 person